As humans, we enjoy feeling understood and discovering new things we’ll love. Companies recognize this and leverage recommender systems to enhance our experiences while maximizing profits. Recommender systems are machine learning algorithms that use data to recommend items to users. As a data scientist, there are few things more satisfying to me than a well-tuned recommender system. I’ve been particularly fascinated by Netflix’s and Spotify’s algorithms for years now. How do they learn the features that define our tastes? Determine which items to recommend next? Decide what to recommend brand new users, or which users to recommend new items to? These questions drove me to explore the mechanics behind recommender systems. As I’ll explain, there are two branches of these systems: content-based recommenders and collaborative filtering. Let’s jump in.

Content-Based Recommenders

Content-based recommenders are relatively straightforward. Let’s imagine a friend asks you for a movie recommendation. “Well,” you might say, “what sort of movies do you like?” This is the basic logic of content-based recommenders. The first step is to determine the common characteristics of items a user enjoys. Continuing on with movies as our example, we could ask our friend whether they prefer comedies or horrors. Do they hate long movies? Is there a certain director they enjoy? These are the features that will help us determine what to suggest next.

In practice, this relies on calculating the similarities of different items. The recommender system builds a profile for each user using the features of items that they have previously enjoyed. The specifics of how to determine whether a user enjoyed an item depend on your use-case, but a common heuristic is whether they purchased an item and/or rated it highly. There are also implicit forms of feedback, such as watch time or repeat viewings. The features of these items can be represented via text embeddings (see last week’s post for more details), one-hot encoding, NLP techniques such as TF-IDF, etc. Once the features are represented numerically, we can calculate the similarity using measures such as cosine similarity. New items are then recommended based on how similar they are to items in the user’s profile.

Collaborative Filtering

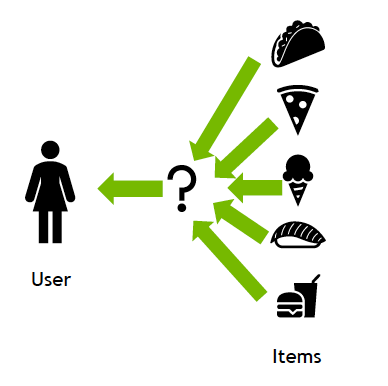

Collaborative filtering doesn’t require any knowledge about the items it’s recommending. It relies solely on user preferences. Returning to our example, let’s now throw another friend into the mix. Your two friends have very similar tastes; they both love lots of the same movies. With this information, we know that if Friend A loves Star Wars, Friend B is more likely to enjoy it as well. Collaborative filtering is this idea at scale.

There are two sub-branches of collaborative filtering: memory-based and model-based. Memory-based methodologies include user-user and item-item recommenders. User-user recommenders calculate the similarities between users, recommending items enjoyed by similar users. Item-item recommenders calculate the similarities between items, recommending users items similar to those they’ve enjoyed in the past. Instead of calculating the similarities between items using features as in content-based techniques, item-item filtering calculates the similarities using previous user interaction patterns. While relatively straightforward, these approaches are rarely ideal in the real world. They struggle with larger, sparse datasets, and user-item datasets are often large and sparse. For example, I recently created a recommender system based on scraped Letterboxd ratings. The data include 1,000 users and over 100,000 unique movies, meaning each user had tens of thousands of movies that they had not seen. Situations like this are where model-based approaches thrive, as they reduce dimensionality and generalize better for sparse data.

The most well-known model-based collaborative filtering technique is matrix factorization. Matrix factorization decomposes the user-item matrix (where your data is represented with users as rows and items as columns) into latent user and item vectors. This decomposition can be performed using techniques like Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) or Alternating Least Squares (ALS) to capture latent features (hidden patterns) in the data. You can also identify these latent features with neural collaborative filtering (NCF), which learns user-item interactions via neural networks. Instead of factorizing the interaction matrix explicitly, NCF learns latent representations using dense layers and activation functions. The technical implementation of these techniques is beyond the scope of this article, but if you want to learn more check out my letterboxd recommender repository on GitHub.

Hybrid Approaches

So which approach is best? As you may have guessed, it depends on your data. If you have no item metadata, you’re limited to collaborative filtering. If your data is very sparse, matrix factorization or a deep learning approach such as NCF is probably your best bet. But most sophisticated recommender systems ensemble multiple algorithms to play on each other’s strengths. For example, in my recommender system, I tried to imitate Netflix’s model of having “For you” recommendations as well as “You may also like” suggestions after finishing a movie. The “You may also like” approach mimics content-based filtering, while “For you” aligns more with collaborative filtering. You could also use a content-based approach to put together a list of similar movies and then a collaborative filtering method to rank the films by the user’s predicted rating. Another potential feature could focus on newly added movies, and use a content-based algorithm for recommendations since the new movies don’t have any user-item history. There are so many possible approaches, and I love the room for creativity that recommender systems provide. And as in many machine learning problems, an ensemble approach is often the best one.

This article barely scratches the surface of important recommender system concepts. Stay tuned for future posts on this subject, where we’ll discuss the cold-start problem, evaluating recommenders, and more.